The house that I lived in while I was in my early teens was built in 1860. It had some structural oddities.

I’d say the most odd oddity was the fact that, to get to the master bedroom, you had to walk through one of the other, adjoining bedrooms. As this was probably more inconvenient for my sister than for myself (my parents always cut through her room instead of mine), the oddity that caused me the most anxiety was my room’s complete and total lack of a closet.

By this, I do not mean that the room was lacking in “closet space” (indicating that closet(s) were present, just small). There was no closet. At all. My sister didn’t have one either.

Instead, we each had a wardrobe. But it could just as easily have been an armoire. Or chifforobe. Or even a clothes press.

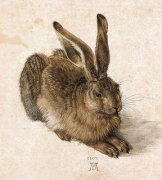

If you give people a picture such as this one (of a way fancier wardrobe than I had, by the way):

You get things like wardrobe, armoire, chifforobe, and clothes press, and, in addition, terms such as cabinet, bureau, closet dresser, cupboard, and shift robe. I know because that’s what I did and those are some of the responses that I got.

Wardrobe is a good follow-up to chest of drawers, as the two forms are linked by a common ancestor – the cupboard – which is basically a wooden box turned on its side with shelves added to the open space. The rudimentary cupboard form becomes, in its medieval life, the press, which is a simply constructed, sometimes painted, and often massive, cupboard.

The press form acquires different names and iterations as it travels across cultures, and several of this form’s more specialized descendants can be observed – both structurally and linguistically – within the history of American case furniture. The initial offshoot of the press appears to have been the wardrobe form, consisting of a cupboard stacked atop a chest of drawers. The name “wardrobe” was taken from the medieval name for a guarded room, usually one adjoining a sleeping chamber, set aside to store clothes, linens, and other valuables.

Wardrobe is a variant of warderobe, which has as a synonym garderobe, an Old French-derived variant used in NE England, which nicely illustrates the historical (and semantic) relationship between the words/concepts guard and ward.

This type of guarded (or warded) room was also commonly used to store armor, hence the French name for the same kind of room and, later, the similar furniture form: armoire.

Eventually the wardrobe becomes a case with paneled doors set atop a drawer, topped by a cornice and set upon feet.

The wardrobe carries on, with this four-part construction, in England, sometimes called a clothes press, a version of the form that often had drawers behind the doors as well as beneath them. In 17th c New England, this piece was also referred to as the press cupboard, and was noted to be “among the most imposing pieces of furniture in early [Am] households”.

Other European forms immigrated to the New World as well. In 17th c Germany, we see the Schrank (sometimes heard as shonk), a massive piece that travelled here with the Pennsylvania Deutch.

The kast (aslo seen as kas) was the 17th c Dutch contribution. In the US, this wardrobe variant was found among the Dutch settlers in New York’s Hudson River Valley area and along the New Jersey Long Island shore. Kast is the Dutch word for ‘cupboard’, but became the designation for a very large (almost wall-sized) wardrobe used by American furniture purveyors.

The French form is the armoire, a piece that is big, often decorated, usually found with no drawer below the paneled doors, and sometimes with no feet.

From 16th c Italian furniture makers, we have the form that Americans called a cabinet. This form, called a armadio or guardaroba in Italian (names that obviously also contain the element of ‘arming’ and ‘guarding’), is a cupboard-like space filled with small compartments or drawers and fronted, once again, by paneled doors.

Thus, to America (and American vocabulary) came various European-inspired constructions, the wardrobe, the press cupboard, the Schrank, the kast, and the armoire, all of which are variations of the basic, medieval ‘cupboard’ form described above.

Continued contact with France and interest in French fashions, especially in areas surrounding Charleston and New Orleans, ushered in a great many French-inspired furniture forms. These Franco-inspired furniture items include names for all sorts of different pieces: commode, chiffonier, divan, bergere, buffet, chaise, étagère, and recamier.

Speaking of cultural influences, New Orleans specifically served as the cultural hearth of the Gulf States area, and its cabinetmakers, including the famous “freemen of color”, produced a wardrobe form made in “Creole style” – a blend influences from the Caribbean, Louisiana French, and other Anglo-American styles. One rather ornate form was the New Orleans cabinetmakers’ signature piece: the armoire. In this area, even the trusty chest of drawers fell to the “ubiquitous armoire” as the chosen piece of household case furniture. In New Orleans, the traditional chest of drawers form was also passed over in favor of the semainier, a tall, slender, seven-drawered chest called after the French semaine, “week”.

I think the term semainier contributed to the geographical spread and longevity of “chiffonier.” Chiffonier is a term found in the Linguistic Atlas data as a response for both the ‘bureau’ and ‘wardrobe’ questions. ‘Chiffonier’ was borrowed from French, derived from chiffon for ‘rag.’ A chiffonier is a tall, slender chest of drawers, a description very similar to that of a semainier; in fact, the Dictionary of Furniture defines the ‘semainier’ as a “chest of drawers, often a chiffonnier, with seven drawers”. Structural similarities coupled with phonological similarity (“shiff-own-yea” and “se-man-yea”) could have led to the ‘merger’ of the two forms and terms into one.

In addition to a host of French-descended items, there is one other ‘foreign’ language influence on the Linguistic Atlas ‘wardrobe’ responses worth mentioning. There was one Pennsylvania Dutch speaker who responds to the “wardrobe question” with Kleidereck (German for ‘clothing corner’, another example of loan translation).

History also gives speakers options to use a variety of productive word-making processes, such as blending (creating a portmanteau). One of the blends that we see amid the Atlas responses to each of the case furniture questions is wardroom, which was used exclusively by Gullah speakers, a blending of “ward” from wardrobe with “room”. Wardroom is a naval term for the ‘officer’s mess’, though I am inclined to think the use of wardroom by Gullah speakers as an independent invention.

Chifforobe is a blend of wardrobe and chiffonier, a form that may reflect function. A chiffonier (the smaller, slighter stack of drawers) combines with a wardrobe (two tall doors and clothes rack inside) to create the chifforobe, a wider piece with two tall doors, but shelves on one half inside and narrower rack for hanging on the other.

Other blends in use include robeward and sideward. Between blends like these and the plethora of compounds (such as upright bureau, box wardrobe, etc.), what strikes me here is how productive English speakers are in their naming of household items. The fact that furniture designers (new and old) have also been highly productive has probably further encouraged the creation of names that reflect slight variances in shape and function. The seemingly endless combinations of doors and drawers that the basic ‘wardrobe’ shape can hold have left their mark on the American furniture lexicon.